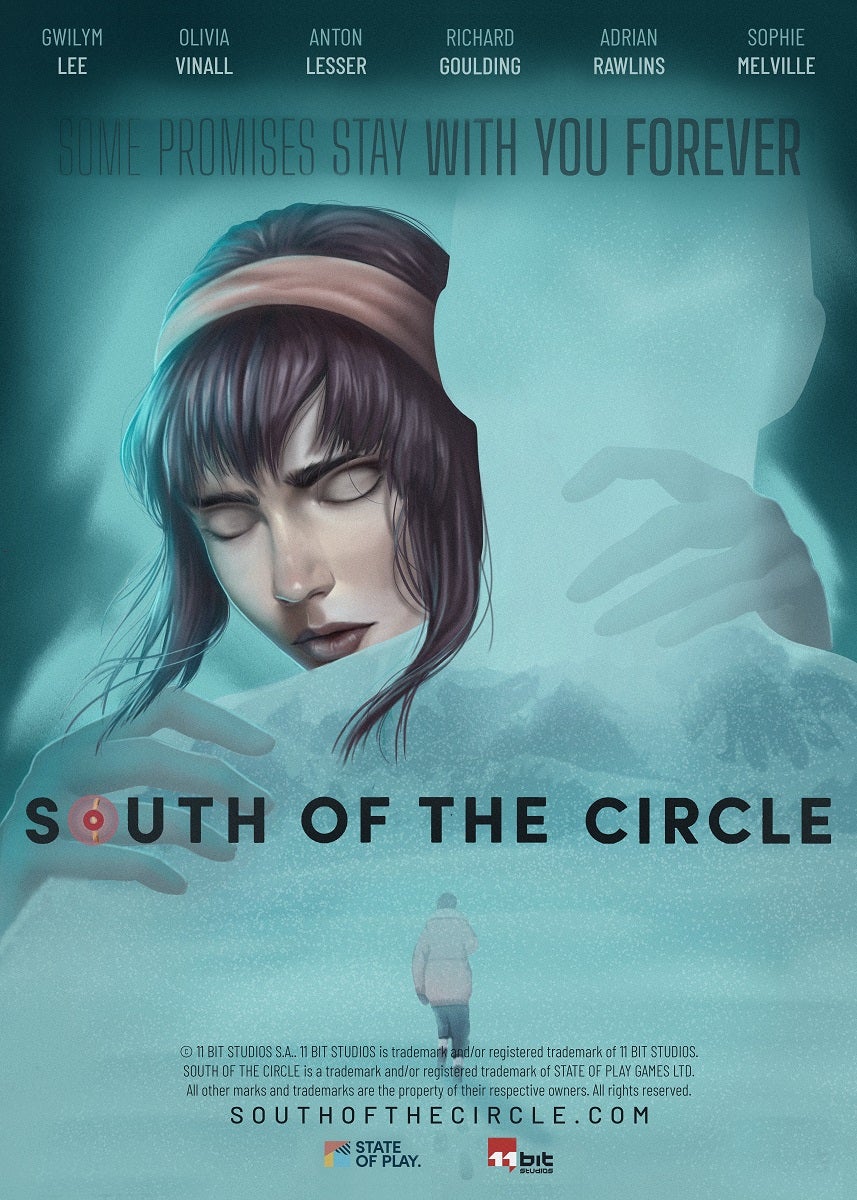

The problem with this is disjointedness: pauses in conversations where there would normally be none, mismatched tone where there wouldn’t normally be any. Sometimes it’s obvious, sometimes it’s not. And however good the performer - and direction and sticking back together - the result is never quite what it’s aiming to be: natural. Because it’s not. South of the Circle got me thinking about this again. It’s a smallish game that came out on Apple Arcade a couple of years ago and resurfaced on PC and Switch this week, and I’m very glad it did, because it has some of the best performances in a game I have ever witnessed. Some of it’s to do with the cast, for sure. They’ve all made a name for themselves in Hollywood. They are Anton Lesser (the creepy Maester Qyburn from Game of Thrones), Adrian Rawlins (Nikolai in Chernobyl and also James Potter in Harry Potter), Olivia Vinall (Laura Fairlie in The Woman in White), Gwilym Lee (Bryan May in Bohemian Rhapsody), Richard Goulding (Prince Harry in The Crown), and Michael Fox (Andy Parker in Downton Abbey). And obviously their hiring is a big draw because they’re advertised like movie stars on game artwork. But another large part of it is to do with how the game plays. South of the Circle is an interactive movie game so a lot of it plays out without you doing anything, and you jump in to make decisions in dialogue and control some light exploration. There are dialogue choices, then. But not all dialogue is multiple-choice: sometimes there’s only one option and when there are multiple, the impact you can have on the overall outcome is incidental. Clearly, there’s a story the game wants to tell and you can’t get too much in the way of it. The game also chooses dialogue options for you if you don’t do anything and moves you towards destinations automatically, leading to a sense that, sometimes, it’s playing itself. So on the sliding scale of interactivity, it’s going the other way. But the trade-off is fewer interruptions and this ability for scenes to flow. I wasn’t actually sure how they recorded the game until I came across a ‘Making Of’ interview with the founders of developer State of Play. And it was a joy to hear that, above all else, they wanted the acting to feel real, to feel natural. They wanted characters talking over each other; they wanted them to start sentences they didn’t know how to end. And they then rehearsed scenes rigorously to find this, as groups, and captured that whole performance for the game. The result speaks for itself. It’s not showy or gaudy but it’s, gently, real. It’s convincing and believable. It actually reminds me a lot of watching a play (I think it’s the length of the scenes and the contained spaces the actors are often in). True, a play couldn’t as seamlessly snap between timelines in the way the game does: following a character through an Antarctic waystation door to a Cambridge University room in a fraction of a second. But a play can, perhaps more importantly, pull you into the emotion of it all. And it’s this essence that makes all the difference. Because while there is a Cold War story playing out, it’s the human interactions and emotion within that that really carry the game through. It’s watching two characters stumble closer and closer until one of them takes an emotional leap to make the relationship something more, then the tender promises they try and hold it together with. It’s watching a stranger take a risk to help another in a time of desperate need. It’s feeling indignity when people rise up against inequality. It’s these human moments, powered by the superb performances, that make South of the Circle as moving and successful as it is. But it’s not as interactive as it could be. So is more interactivity always better? It’s a tricky one.