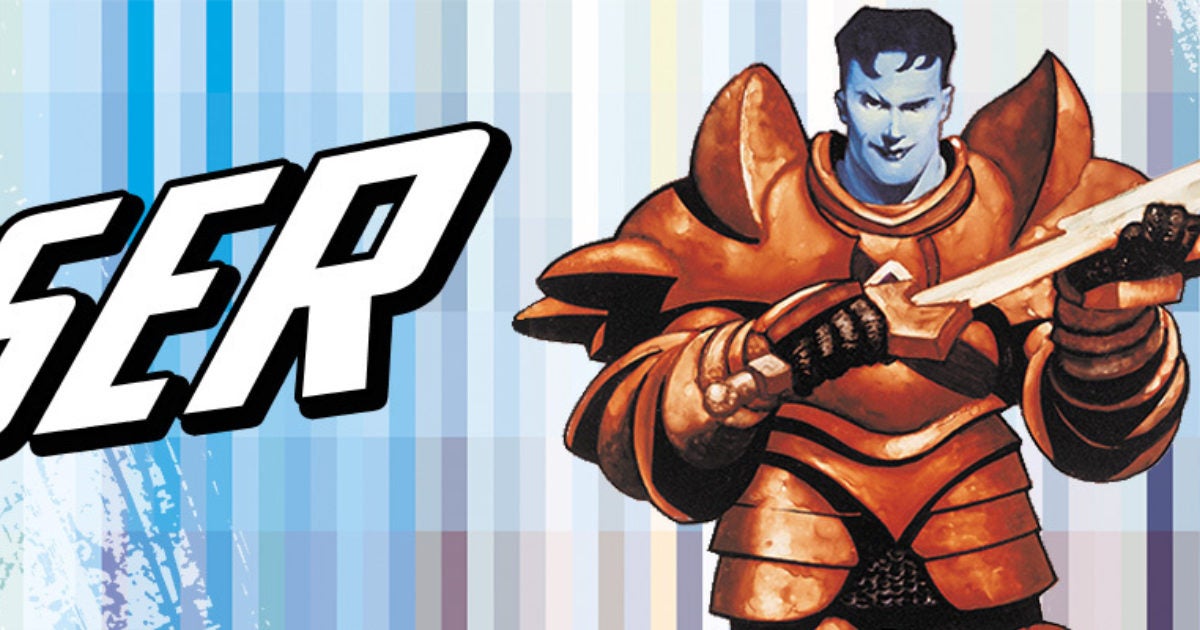

And while we have you here, if you’ve been eagerly awaiting a restock of Eurogamer’s Pride t-shirts, we’re happy to report that more - in two ravishing variants - are now available for purchase. All profits will be split between LGBTQIA+ charities Mermaids and Mind Out. It won’t come as a surprise to anyone with even passing familiarity with the LGBTQIA+ community that self-expression is incredibly important to queer folks. It’s all too common for us to spend much of our lives forcibly suppressing our identities, hiding who we are from the public, our friends and family, or even from ourselves. Equally unsurprising, then, is the fact that we often turn to the internet when looking for spaces where we can belong. From modern social media stretching back to the bulletin boards and chat rooms of the early commercial internet, queer folks of all stripes have used this wondrous series of tubes to find information, resources, community, or just places where we can be ourselves. I was fascinated by the internet from an early age, long before home access or even internet cafes were commonplace. Features in Amiga Format, TV coverage, and a treasured visit to an exhibit at the Science Museum that gave me my first, bumpy ride down the information superhighway maintained that interest until we got a PC with a dial-up modem at home, when I was in my mid-late teens. Of all the promised delights of an interconnected future, it was the simple MUD that I wanted to experience the most. Multi-user dungeons were (and still are) text-based roleplaying spaces built around chatrooms. MUDs evolved, frequently adding built-in game mechanics and collecting a variety of inscrutable acronyms like MUCK and MUSH, before slapping on graphical interfaces - like a fish with lungs and rudimentary limbs - becoming the first MMORPGs. It wasn’t just MUDs making this evolutionary leap either, with less explicitly roleplay-focused spaces like chat rooms gaining graphical equivalents too. In the decades since, many variations on the theme have appeared, from long-running services like Second Life to more recent inventions taking advantage of other technologies, like VRChat. While not strictly speaking games, they’re certainly game-adjacent and function as platforms for people to run and play games. And, as with the internet at large, they’re places that queer people can gather and be ourselves, whether we know that’s what we’re doing or not. I am a transgender woman. That means I was raised as a boy and lived my life until a little after my thirtieth birthday as a man. I was never a particularly masculine child, but neither am I a stereotypically feminine woman. I knew from a very early age that, given the choice, I would prefer to be a girl. Of course at that point I hadn’t heard the word transgender, nor transsexual, the earlier term that has since fallen out of favour. I was vaguely aware that having a “sex change” was a thing that people did, but I never connected the dots. People are given very little guidance on what is or isn’t normal unless we obviously deviate from that baseline. I never voiced my desire to be a girl, although I frequently dreamed of doing so, so no-one was able to tell me it was particularly unusual, let alone something I could act upon. The first time I encountered the idea that I could use online spaces to be the person I wanted to be, that I really was, was in the pages of a comic series called User. Written by Devin Grayson, with art by John Bolton and Sean Phillips, I stumbled across it in 2001 at the tender age of 18. It’s a series about a young woman called Meg who uses the character of a male knight to escape her unhappy life and carve out a new one online. It touches on some weighty topics, but the ending is ultimately a happy one and I highly recommend it as a window into the early internet, if nothing else. It was shortly after reading User that I started to experiment with playing female characters in online spaces. I kept it secret, for the most part, as it was frowned upon in most circles. The supposed vast male majority in gaming, combined with the often self-deprecating view of gamers as awkward, sex-starved geeks, led to various stereotypes and jokes. With voice chat becoming the norm being years away, there were plenty of stories floating around of men pretending to be women in order to exploit their nerdy compatriots, on top of the general misogyny and homophobia that appears whenever men do anything considered effeminate or unmanly. “Many Men Online Role Playing as Girls” was a popular joke about MMORPGs for years. I instinctively recoiled from such suggestions, especially from allegations of intentionally misleading people. “It’s just roleplaying!”. “If I have to stare at an arse for hours on end, it may as well be a female one, right?”. I know for a fact that I’m far from the only person who has spoken those words in jest and later come out as transgender. But the more I did it, the more comfortable it became. When I started exploring Second Life, I had a female persona and avatar from the outset. Sure, I still made excuses to others, and to myself, but I didn’t even hesitate. Why would I want to be a boring boy when I had the choice? Girls looked better, had better clothes (seriously, check out the amount of female clothing on the Second Life marketplace compared to outfits for male avatars), and it just felt right. It still took me a while to start connecting dots, even after talking to people who had realised they were trans through very similar circumstances to mine. Even then, I rejected the idea of transitioning. I was too tall, too big, too fat. All the trans women I saw in the media had either done so very young, or much later in life. I didn’t start seriously considering transition until I started to see trans women of a similar age to me become prominent in indie gaming circles. Representation is vital and seeing myself in those trailblazing people was a huge deal. I first came out as trans to my immediate family just a few months after my thirtieth birthday. I spent the weekend before making a TWINE game while sorting through my feelings. I believe it’s still out there on the internet, somewhere. Things have changed, for better and for worse, in the near-decade since then, both for trans people and virtual spaces. The proliferation of voice chat makes communication quicker and easier, but can also make it harder for trans people to interact without outing ourselves. VTubers become more and more popular, legitimising and normalising the idea of virtual identities in the mainstream. VR becoming more commonplace offers new possibilities, as does the number of companies rushing to establish themselves in “metaverses” (a word I can’t type without cringing) but the concentration of the internet into walled gardens isn’t necessarily a good thing for personal expression and self-discovery. It doesn’t help that so many of these spaces seem to be doing things so much worse than creaky old Second Life, a platform that will be twenty years old next year. Wherever technology creates new frontiers for humanity, those who are deemed deviant or outcast will flock to this territory in search of homes that they have otherwise been denied. In the (almost) forty years I’ve been around, these spaces have expanded and changed in ways that I could barely have imagined when I first encountered them. Who knows what they will look like in another forty?