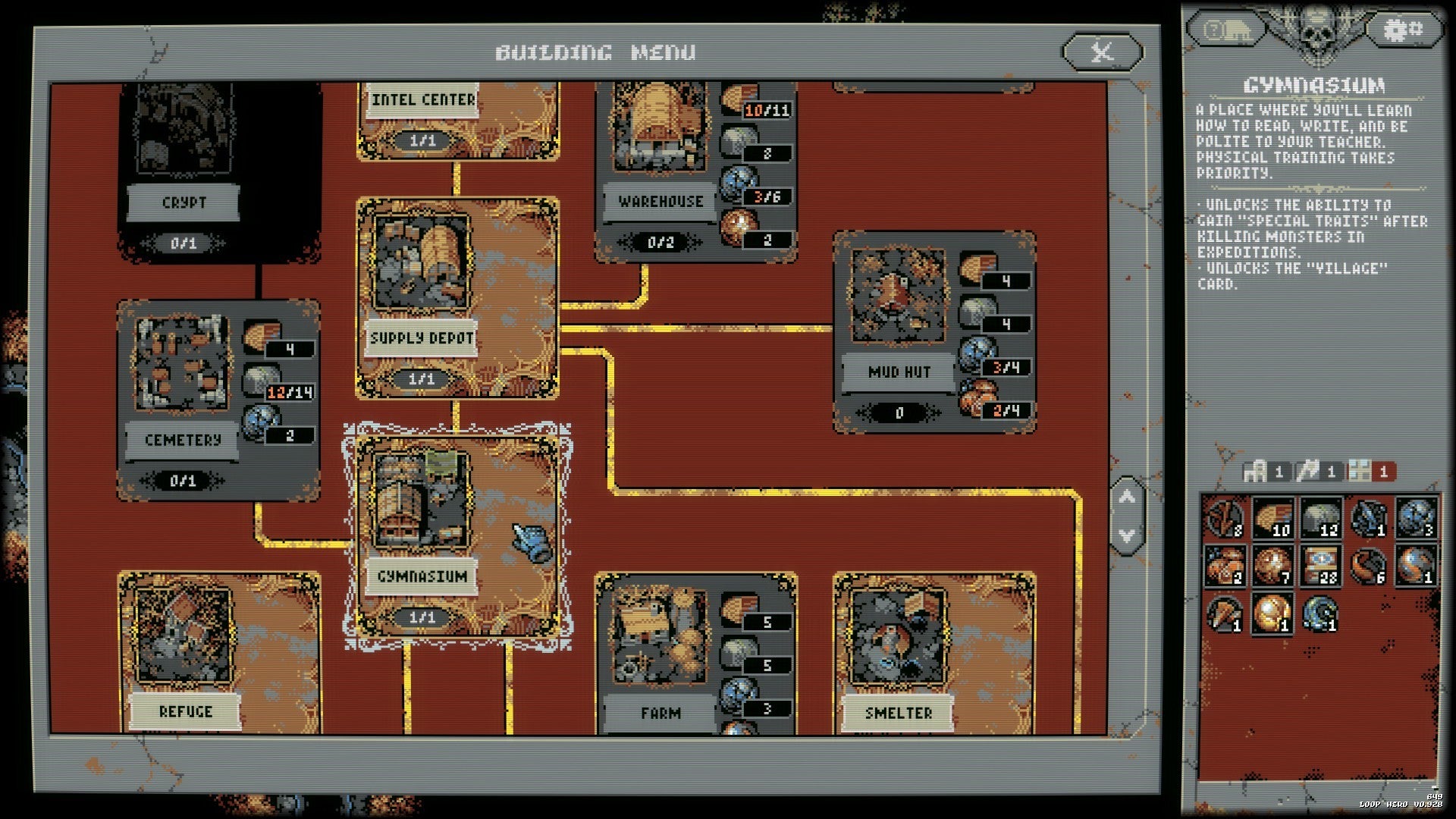

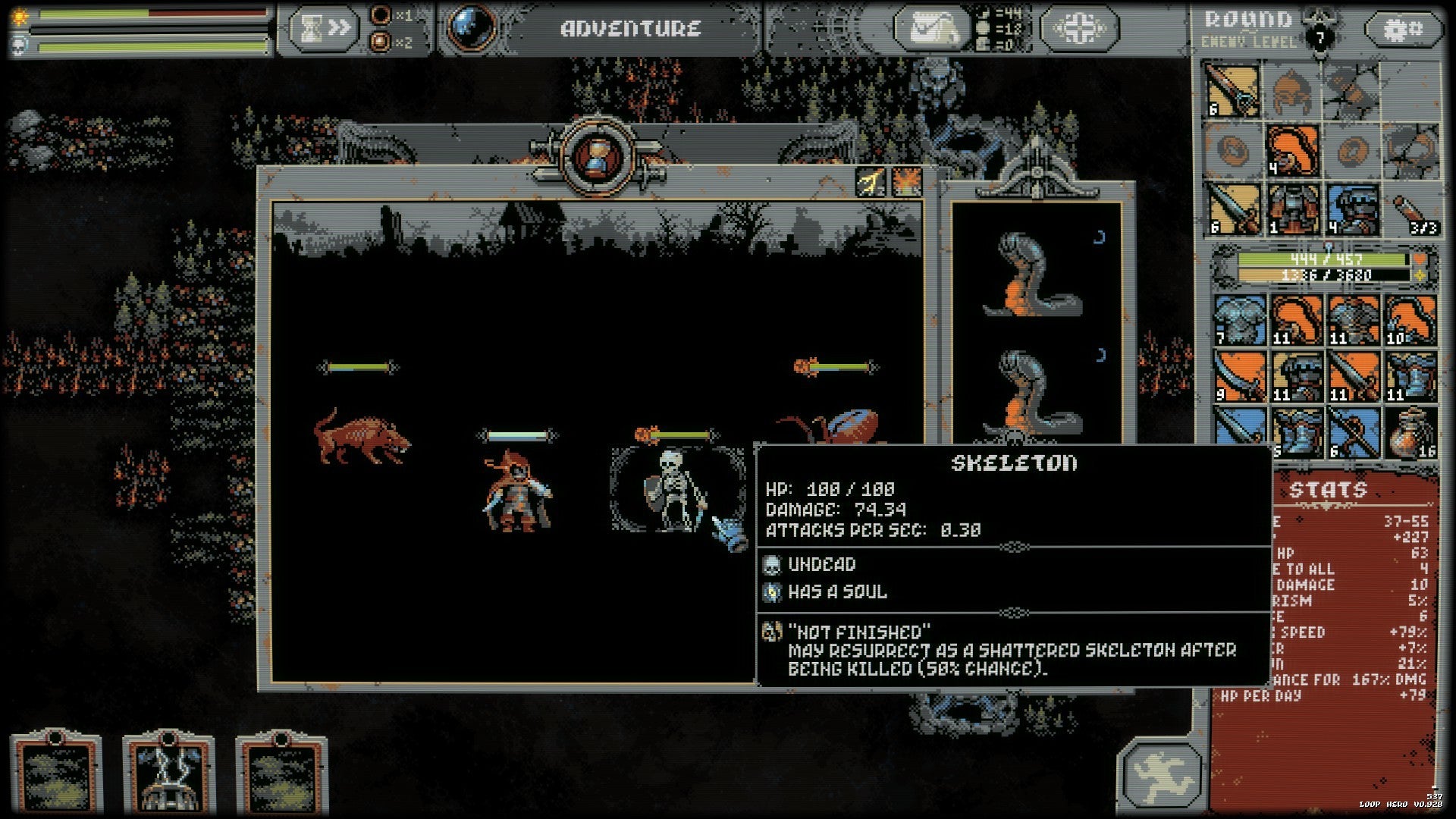

In Loop Hero you don’t walk in circles, you walk in loops. Each procedurally created path leads back to its own beginning, but the shape will have a few kinks and bends. It reminds me a bit of those natural artworks formed by the discarded rubber bands that the people who deliver post leave behind them as they make their rounds. Rounds which are frequently loops, I’ve just realised, and not circles. Loop Hero is quite simple really, but it can be a faff to explain. Let’s get to it. It’s an RPG, with all the monsters, loot, quests and bosses you might expect. There’s even a story - quite a good one, about a world that has ended but could yet be rescued, brought back to life one chunk at a time. It has heroes and classes and all that stuff, but what marks it out, what makes it different, is that it doesn’t let you directly control the hero. Not really. You can’t fight their battles or choose their next objective. Instead, you keep them kitted out with the best stuff and you start them and stop them as they walk around their loop, a tiny little pixel person in a dinky pixel world, a charismatic presence straight out of the Commodore 64. The world is a loop here, that rubber band the postie left on the floor. At first there’s not much to it, just a few low-level enemies that your hero whacks as they walk their circuits. Enemies drop loot, which you can pick through to improve your hero’s stats, and they drop cards, and cards are more interesting. Cards allow you to piece back some of the world. Take the world of the loop. You might place swamps on it, or graveyards. You might push vampire castles up against it, or light it with beacons. Those are just early cards. All of this stuff will spawn new monsters on the loop for you to bash, or will change the way things work on tiles. A good card might make you attack faster! A bad card might spawn a weird time-travelling horror who turns up to make stuff difficult. But is that really a bad card, or is there something great about it, waiting to be understood? Outside of the loop you can also place cards. You can pull the world back into existence, one rock, mountain, meadow or tree at a time. This stuff has purpose too. Certain features of the landscape might boost your HP. Others might regenerate HP. All of them will give you resources - which we’ll get to in a bit if I remember to mention it again. And there’s a puzzle to the placement. Which feature likes to be next to which other feature? Which bonuses can you find in arrangements? What’s the optimal layout? How to make the meadow bloom, the rocks into a proper mountain range? While all of this stuff is going on, don’t forget the loop. The stuff you place away from the loop will affect that too. Mountains are great for HP, but they cause new enemies to spawn on the loop, just like villages and fields on the loop are great for HP but attract their own horrors. As the cards grow and your choices become more complex, you’re really programming: you’re programming the horrors your hero has to face. And you want them to face these horrors because defeating horrors gives you better loot and better cards. You are stronger and have more resources. Those resources! Every time you reach the start of the loop again you have the option to leave with all the resources you’ve collected. These tie into a kind of base-building game that permanently opens up new stuff for your hero, including new cards and fresh classes to try, three in total, each one twisting the game in odd ways. But if you leave the loop to cash out, when you return you have to start over again from scratch, aside from that incrementally improved base of course. That means rubbish gear. Low-level enemies. Nothing in the world. Looping and looping and looping until things start to get tasty again. The reason you’re doing all this is because, eventually, when you’ve placed enough cards and brought enough of the world back together, a boss will appear. If your stats are good enough you can auto-chug through them and onto the next bit of game, and then the next boss, and the next. Again, though, risk and reward: die to a boss - die to anything - and you lose most of the resources you gathered while looping. And, you know, you have to start again with rubbish gear and low-level enemies. What a drag. This is the point at which Loop Hero unfurls with additional complexity. You earn perks. There are quests. You dig down into the stats and the way each class works and discover a game that is filled with fiddly richness waiting to be teased into the light of understanding. All of this, though, is channeled through the loop. That’s where it all makes sense - where the foot meets the path, where the sword meets the slime, where your hero encounters the world you are building just for them. There is more, but I’m going to stop with the explanations. And this is the strange problem with Loop Hero - although “problem” might be pushing it. Whenever I try to tell someone about this game it always devolves into telling them how it works. You have to get mechanical very quickly, because the mechanics - the way it foregrounds or backgrounds elements from RPGs that we’re all familiar with - are where it truly lives. It’s a game about games, a commentary on compulsion as much as it is an adventure in itself. And I mean “as much” - it’s still a wonderful adventure for anyone who loves numbers that go up. But yes, sort of the secondary-text industry. It’s a thesis on games - and players - as well as being an actual game. What do I think about it? I am as compelled and as drawn in and as frustrated with the grindy bits as anyone, I suspect. I love the fact that it reminds me very strongly of Monopoly - you do laps of a track filled with the ever-changing possibility for glory and for disaster, and a lot of it is your fault - and I love the fact that it’s ultimately a game about the two ends of a pencil - the sharp gritty point and the eraser, creation and destruction and how they affect one another in playful ways. That’s the theme, the mechanical thrust, and also, I suspect, a lot of the direction of the design impulses that brought it all together. But what do I know. I actually think Julian Barnes said it best, although as far as I’m aware he wasn’t talking about Loop Hero at all. (He was talking about Enter the Gungeon lol.) In the introduction to Keeping an Eye Open, his book of writing on art, most of it French, he says, “In all the arts there are usually two things going on at the same time: the desire to make it new, and a continuing conversation with the past.” That’s very Loop Hero, isn’t it? Pixel art in the aid of a sort of laser-sculpted RPG construction kit freshly delivered from the day after tomorrow. A deeply knowing game whose designers pluck at your obsessions as if they’re idly reaching into a piano case to twang the strings - but that still makes you fight slimes because fighting slimes is brilliant.