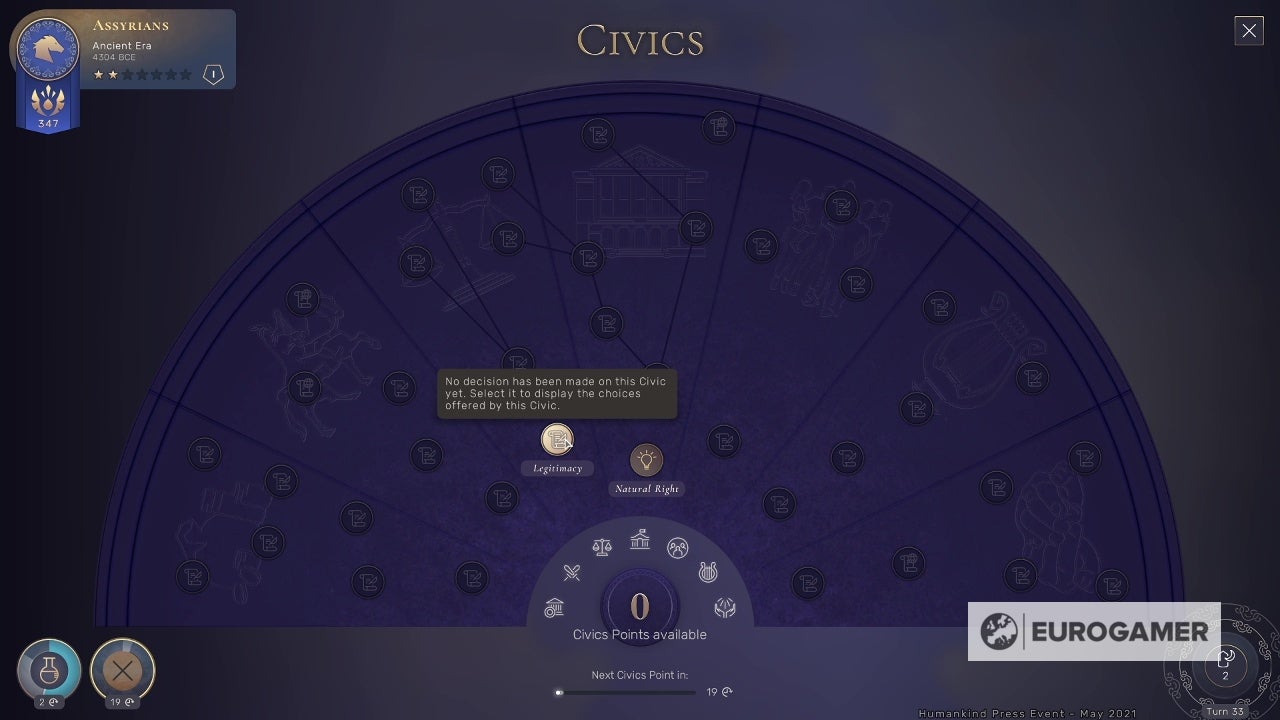

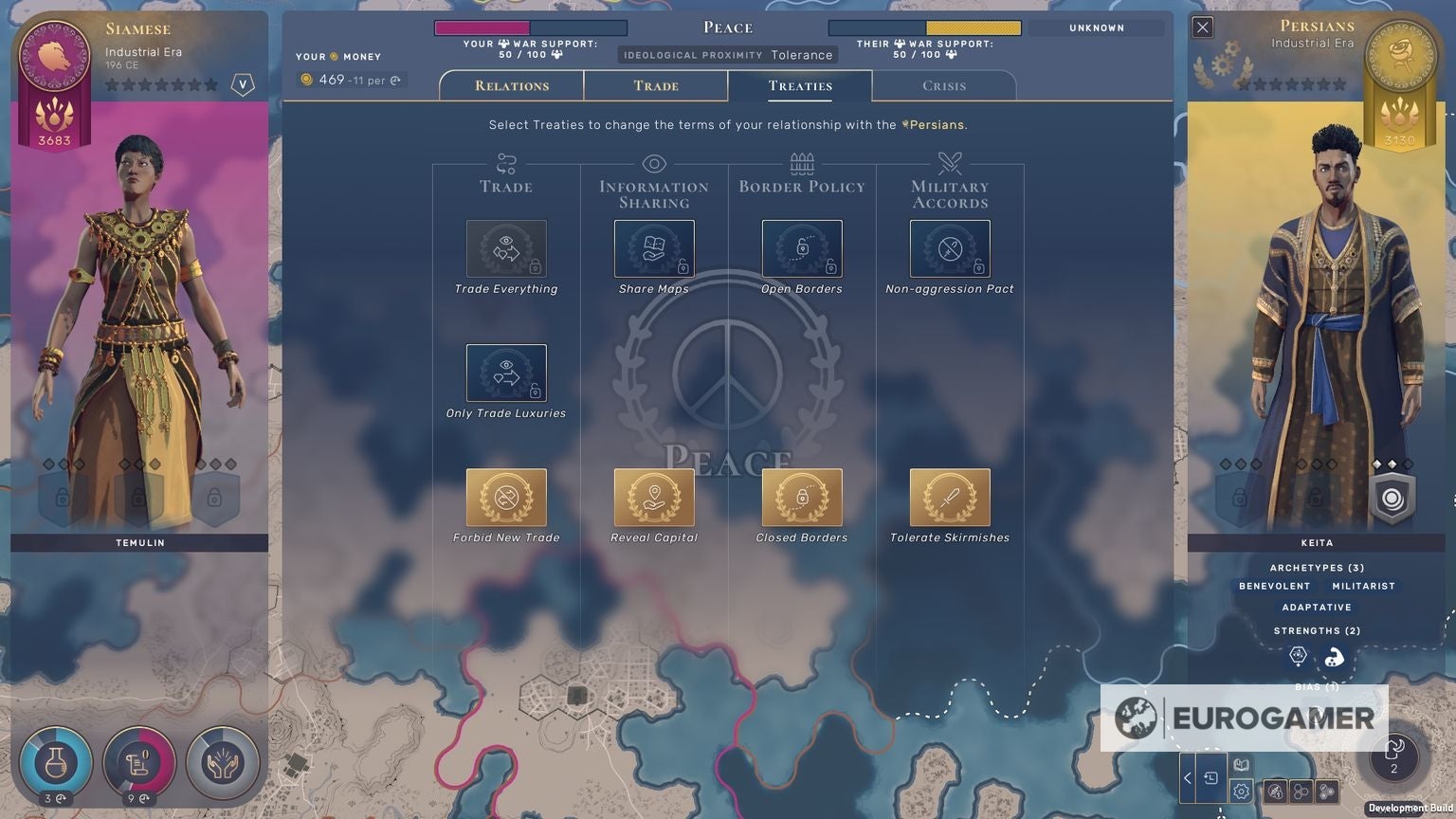

The thinking about it, obviously, is the joy of any good 4X though, and that too is the special pleasure of a new one. I don’t know the way from Masonry to Telecommunications anymore, I have to discover it - re-discover it, really. Like digging up an old Roman path. Anyway, this is what I’ve been thinking about while playing Humankind for a lovely dozen or so hours, and for a time after it. Humankind is a game full of systems and empty space. The things to think about, deeply and lengthily, and the time to do the thinking. It’s wonderfully moreish, and importantly now quite fully-formed. It’s been roughly a year since I last previewed Humankind, and it’s been delayed by a good year or so in that time too, but the game now feels close to the real thing. The changes between now and then are numerous, but also plenty of them are very small. Talking to Amplitude studio director Romain de Waubert and executive producer Jean Maxime-Moris, I got the sense that there are too many of those little changes to count. “Balance,” was one that came up an awful lot, with Humankind’s tactical, turn-based battle system tuned up repeatedly over the months since I last tried it, as well as the in-game economy. The bigger things are the fleshing-out of the religion and civics systems, two things that weren’t even in Humankind when I last got hands on it, as well as the late-game industrial age, which I still didn’t reach in this playthrough anyway. Religion, in brief, is looking good but also maybe just a little lightweight. It’s very similar to religion in Civilization 6, if you’re familiar (get ready to hear that a lot by the way), in that you pick one after triggering something in the early game, exert religious pressure on nearby people in various ways, and unlock various “tenets” as you reach certain milestones, in this case a certain number of followers. You choose the tenets from maybe a dozen or so each time, and crucially they all play into the other systems of the game. Religion is basically a series of passive buffs, stackable enhancements to how much money you earn, or food you farm, or how quick you build things - a weird way of thinking about religion, when you think about it actually, “Thou Shalt Min-Max Thy Influence Score”, but a traditional one for the genre. The sense of simplicity just comes from the clarity of how it’s presented. In Civ religion is a simple system buried in nomenclature and UI; in Humankind it’s almost identical, but you can actually understand it, and in turn understand that there’s not a huge amount to it. Much more exciting, for me, is the civics system. Again like Civilization this is a kind of secondary tech tree, alongside the actual science-based technology one, but it avoids that whole STEM vs. humanities rivalry by structuring the tree itself a little differently. Throughout the game you’ll trigger dilemmas, choices between two options that sound like prompts for a bit of entry-level political philosophy coursework. The Founding Myths civic, for instance, asks, “By what right do we rule?”. The first option: Natural Right, which suggests inherent dominion over the land and beasts (very Old Testament that, by the way - there’s a whole corner of theology dedicated to whether the use of the word “dominion” implies rightful control over animals or a duty of care). The other option, Divine Mandate, says supremacy is ordained because we’re the “chosen ones.” The mechanic, meanwhile, is all in the kind of meta layer that the civics system has. The civics section has four sliders, called Ideologies, where a point moves between left and right on the scale. One is Collectivism on the left, Individualism on the right. The next is Homeland and Internationalism, the next Freedom and Order, and the last one Tradition and Progress. The decisions you make with which civic you choose in these dilemmas will give you a direct outcome (+5 Stability in your cities, say, reducing the likelihood of rebellion) but will also impact your Ideologies, the “Natural Right” option moving the dial a little further towards progress, “Divine Mandate” further to tradition, and then your Ideologies will impact the various resources of the game once again, a more progressive society granting bonuses to Science production, for instance, but losing out on the Stability of a traditional one. These are also enhanced by smaller, narrative-style dilemmas that seem to emerge at random too. Now and then you’ll get a pop-up asking you to decide what to do with some villagers who are getting freaked out by a spooky cave: do you send a group to explore, nudging society towards collectivism, or get someone to dress up as a monster, perpetuating folk lore and so nudging the other dial towards tradition? As Maxime-Morris puts it, “there’s the sense of, well, if I want to maximise that gameplay benefit, then I need to remain aligned with my values, but at the same time am I role-playing or am I just min-maxing? And so am I going to make that terrible-sounding choice just because it yields more food? Or do I want to actually impersonate a leader that is better than the sum of my parts?” Either way, you get the sense that this is where Humankind does the most of its chin-stroking about how the people of Earth organise themselves, how they do - or ought to - behave. The game itself is fundamentally and purposefully detached. This is because its win condition is still Fame, a numerical score awarded for achieving certain feats during each Era. The person with the most Fame at the end of the game wins, always, and so, not to get all Kant on you, that means the scientific, or militaristic, or ideological achievements of your civilization are all a means to an end, rather than ends in themselves. It’s only the principle, I think, that makes me a little wary of it as a system, because while it’s conceptually a little simple, in gameplay terms it works quite nicely. A feat, like destroying three enemy units in battle, grants you an era star, like a good little student of war, and an era star grants you some Fame score. Your progression to the next era, like Classical or Industrial, is gated by a certain required number of stars, but you can choose to stay in your current era and hoover up more stars - more Fame - if you like. The risk there is that Humankind has a flexible approach to civilizations and cultures: when you move through eras you choose a new culture to adopt - basically a playstyle, like the expansion-oriented Assyrians, building-first Egyptians, and so on - and once one’s been adopted by one player it can’t be chosen by anyone else, so by waiting in an earlier era you could miss out on a favourite. The principle of all this Fame business is interesting, though. At one point several years ago, Maxime-Moris explains, the team was thinking about calling Fame something else, like Progress. “And then we talked to our historians, and you have, well, ‘Here’s what comes with this word, there’s this history of usage of that word, this is what it means, this is how it is Western-centric.’” Going with Fame as that specific word was an intentional way of keeping it neutral, but then also neutral in terms of how you play the game, too, so its flexible enough that your “fantasy,” as Maxime-Moris puts it, of being able to be whatever kind of leader or society you want, always remains intact. There are also hints from Maxime-Moris that your Fame (or lack thereof) will have a knock-on, contextual impact in-game as well. Other civilizations already respond to you contextually in terms of things like jealousy or admiration impacting diplomacy, but he teased “some fun stuff coming in there” with regards to Fame before the game launches, and again that ties into why they kept the key goal of Humankind as neutral as possible. “That’s why,” de Waubert explains, the team didn’t “give words” to you as a leader beyond your Fame score, “to let you define yourself as what you are, and not have the game tell you.” “A lot of the work that is going on in the final stages of production right now,” he goes on, “is to better feedback, the results of your actions, and definitely through text, but also stuff that is coming soon. But basically: we want to trigger immersion, and narrative, based on the context that is around you that you helped create, and in which you acted, and that result needs to be made very apparent to you for that choice to feel meaningful until the end.” Away from all these big ideas, though, the job of any good 4X is to get the little things right. In terms of progress from the last time we played Humankind, Amplitude seems to have done that rather well. One minor gripe of mine was around movement, and the way a single pesky Barbarian chariot could harangue your troops across the map - that seems to have been tweaked in one of those many combat-based balance passes. City management is also quite clear - surprisingly so, for just the second play of a 4X game. Citizens are grown through food and assigned either automatically or manually to generating a certain resource. Districts are ‘unstacked’, going next to one another on separate hex tiles. The balance of resources, very broadly speaking, seems to work well. One area that could do with a little more explanation - via tooltips, ideally, because what 4X player doesn’t live for a good tooltip - is Influence. Influence is Humankind’s version of Civilization’s Culture. Or more simply put, it’s a resource you earn that has a pressure-like effect on other civilizations. Building cities and expanding in general costs Influence, so the more you have the more you can grow in sheer area of control. It seems to also have an impact on tourism down the line, once you reach that stage. In the early game it just seems to take a little while to get going, with almost nothing that can be built or done to help ramp it up - and then quite suddenly it seems to really get going, with a few stackable bonuses from things like religious tenets all of a sudden clicking into gear. For the moment it just seems both a tad one-dimensional, and a tad under-explained, but hopefully it’ll evolve as the game gets closer to launch. Again though, that’s all minutiae, and those are the things that will change more freely and more regularly as Humankind does approach launch, and likely beyond it. What matters most, as long as those little things are balanced to some extent, is the big picture. This is a game called Humankind, after all. It’s a game about the history of life, the history of everything. What matters most is whether or not it feels like that, and so far it really does.