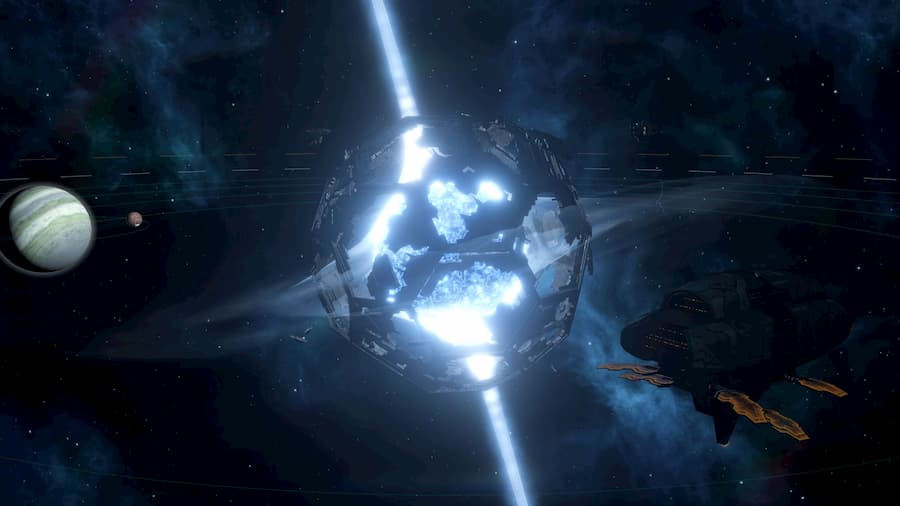

You may know Wewelsburg as the inspiration for Castle Wolfenstein. Reinvented as a set of shooter levels, it has swelled and warped and flourished across generations of videogame hardware and creation tools, from the blue-walled labyrinths of 1992’s Wolfenstein 3D to the campy, steampunk environments of the MachineGames reboots. Wolfenstein deals extensively with Nazi sun worship, plugging it into present-day discussion of the social transformations bred by new forms of energy. In the 2009 game by Raven Software, Black Sun motifs are portals to another dimension, the desolate former home of an alien race named for the real-life Thule Society of Nazi mystics. As with human civilisations on Earth, the Thule rose and prospered by consuming and transforming the energies of their nearest star. It’s the hidden power source for magical mechanisms in the game, such as the solar medallion that lets you shift dimensions. As their sun neared the end of its life, the Thule built a gigantic apparatus to harvest its remnants, with catastrophic results. The Nazis, naturally, are trying to succeed where those long-dead aliens failed. The Thule machine’s wreckage is still visible looming over the game’s final boss fight, spiralling around the dim cinder of the Black Sun itself – Wewelsburg’s floor mosaic transformed with quintessentially videogame literalness into a deathly reactor capable of animating a new age of darkness. Tyrants in every place and era have courted the power of the sun. Napoleon Boneparte called it the “universal giver”, the one god truly deserving of the title. Japan’s national flag is a reference to the Shintō belief in the Emperor as a blood descendant of Amaterasu, sun goddess and latterly, wolf-bodied protagonist of Capcom’s wonderful Okami. Several empires, but most notably the British Empire of the 18th and 19th centuries, have declared themselves “the empire on which the sun never sets”. We meant this literally: Britain’s colonial possessions encircled the globe, so that there was always a portion of British territory in daylight. The sun was for Queen Victoria a fixed point in heaven, a cosmic monster finally stabilised through terrestrial conquest into a kind of imperial starbase. These imperial yearnings rest, I think, on a more fundamental and widely-shared ambivalence. The sun has always been a little dark, as far as carbon-based lifeforms are concerned. It’s a symbol that cuts many ways: on the one hand, an intrinsically egalitarian source of energy, on the other, a token of inescapable oppression; a symbol of bounty and generosity, and a crushing absolute. Secular scientific rediscovery of the sun as a gigantic and in theory, replicable fusion reaction rather than, say, a celestial chariot has made it more comprehensible, but also less sympathetic. Where once people thought of the sun as a creator and caretaker, we now understand it to be an indifferent immensity and ourselves, a morbid extension of its body - undead stardust. We have not grown under the sun’s protection, but evolved to suit the climate it has imposed, and eventually, it will bloat in death and destroy this planet together with whatever remains of its unsightly organic infestation. According to astrobiologists, Earth occupies a “Goldilocks” zone where the pressure and temperature are “just right”, allowing liquid water to exist on the surface. To put that fairytale analogy another way: we are housebreakers stealing food, and just beyond the door stands the bear. Small wonder that, for every ode to the sun as kindly parent, there is an outraged cry in art, religion or science for the sun’s overthrow. The Tang Dynasty poet Li He suggested eating it in his poem “Suffering from the Shortness of Days” - a paraphrase of the primordial rite of photosynthesis, aimed at thwarting the movement of time. “I will cut off the dragon’s feet, chew the dragon’s flesh, / so that they can’t turn back in the morning or lie down at night.” Videogames are a medium characterised by the violent manipulation and consumption of both light and time, and there is a sense that every game featuring the sun as an object is party to Li He’s desire to swallow the hateful thing and bring its tyranny to an end. The obvious practical obstacle is scale. While modestly endowed by galactic standards, our star is too vast to exist in comfortable 1:1 proportion to the solid planetary environments on which games prefer to unfold. I’ve yet to come across a zoom function, rendering engine or set of mechanics that can easily and intuitively encompass that monstrous gulf in size. So most games begin by miniaturising it - not just games set in outer space such as Outer Wilds, whose perpetually exploding, rewinding sun is more of a grossly incandescent asteroid, but third-person action-adventures, from Assassin’s Creed to God of War, where toy effigies of the sun must be covered, uncovered, mirrored and arranged in the correct order. As with Wewelsburg’s Black Sun motif, these puzzles ‘modernise’ older and in many cases, vanquished traditions of sun heraldry and sun worship, reinventing the solar emblems of cultures like the Aztecs as something akin to modern-day light sensors or solar panels, activated by directing a beam. Other games take inspiration from more recent technological efforts to somehow conquer and ingest the sun. The Thule’s doomed sun-harvesting apparatus, for instance, has a real-life precedent in speculative science. In 1960, the US astrophysicist Freeman Dyson proposed encasing our sun in a hollow sphere, fashioned by smearing out the matter of the planet Jupiter. Grand hypotheses like this are shaded by the solar imagery and rhetoric of fascism. Freeman was anti-imperialist, but his description of the sphere isn’t lightyears away from Himmler’s mythologising of Nazi conquest. This shell would, he suggested, provide external habitation for a humanity defined by its desire for “lebensraum” or “living space” - an absent-minded reference to a notorious imperial German policy of territorial expansion, comparable to the settler concept of “Manifest Destiny” in North America. Dyson Spheres are prominent in games about building empires. You can assemble them in Stellaris, slowly filling out the frames of an impossible conservatory to create a cosmic dynamo capable of powering a civilization vast and hungry enough to build a Dyson Sphere. Stellaris is the major influence on Dyson Sphere Program, a graceful management sim in which you transform whole planets into webs of extractors, conveyors and assemblers that spew swarms of solar sails, settling into golden orbit around the star. The two games offer mixed opinions about the implications of swallowing suns. In Stellaris, there’s a touch of dread: any orbiting rocky or terraformable worlds are plunged into darkness. Dyson Sphere Program, however, is oddly without violence. Planets retain their Mario-Galaxy-esque luminosity, beaming complacently as the star is engulfed, glowering behind glass like a child sent to bed before dinner. Helpfully, there are no conscious lifeforms to worry about, no indigenous populations that must be exterminated or rehomed. Humanity itself is at once the prime mover and nowhere to be seen: according to the DSP backstory, we are all sealed away in a virtual heaven powered by solar energy, with a solitary, player-controlled robot left to watch over a cosmos defined as a collection of vast batteries awaiting connection. Dyson Sphere Program presents solar enclosure as not just an energy source, but the solving of the final philosophical equation, a utopian summing-up. Once contained, its suns can be used to fabricate Universe Matrices, an endgame item described as “the ultimate crystallization of the theory of everything, revealing the ultimate mystery of the universe” - every kind of energy, data and matter combined into a glowing cube of cosmic currency. Similar, though rather less pleasant “crystalisations” occur in the Sunless games, Failbetter’s glorious and awful compendium of British Victorian nightmares, which view the harvesting of sunpower as the ultimate blasphemy. Here, stars are gods, a hierarchy of “Judgements” who go by various names during your career as underground sailor and later, captain of a space-faring locomotive. But gods can be replaced. It begins with the Dawn Machine, a rogue artificial sentience fashioned by London’s Admirality to break the darkness of the Underzee. The Dawn Machine is a dreadful spectacle in one corner of the Sunless Seas map, an overlapping framework of glowing circles, like T-virus cells mid-duplication, but it’s a pale reflection of what follows. In Sunless Skies, our original sun has been executed, its ruptured corpse rolling redly beneath the skybound tomb of the Queen’s beloved Prince Albert. In its place, the Empire has assembled a dysfunctional clockwork star. Where the Dawn Machine sought to colonise its creators, sending acolytes to infiltrate the high offices of the Empire, the Clockwork Sun is conscious only that it is as mortal as the hands that built it. It is a livid contradiction, a holy fake, both god and machine. In its fury and self-hatred, it visits terrible transformations on anything nearby, turning ships and their crews to glass and twisting up time like hair. This is the sun of emperors: tortured and objectifying and insane. An ailing centrifugal transaction not of hydrogen into helium but of beings into objects, ringed by smashed and frosted space hulks, tended by rapidly superannuating engineers of flesh and crystal. A shoddily-imagined deity kept thundering and howling beyond its operational term out of a mixture of royal hubris and melancholy English pride in getting through the working day. A barometer for the Empire that waxes and wanes in proportion to Britain’s fortunes elsewhere in the solar system; take the Queen’s side in a quest, and you may arrest or even reverse its decline. The Clockwork Sun won’t turn your own locomotive to glass, but it does inspire Terror, a more insidious violation with all-too-quantifiable effects, clicking up like a Geiger counter as you steam across the heliosphere. As with other abyssal entities in the Sunless series, the player’s own dread is magnified by the game’s perspective, which denies you a glimpse of the seething gyroscopic abomination till you’re right on top of it. Where Dyson Sphere Program cultivates starry-eyed optimism, the Clockwork Sun is a warning about the broader ramifications of solar and fusion energy, aka the cultivation of tiny suns. Both are increasingly offered as the answer to the climate crisis – and also, as a way of avoiding more fundamental and enduring social change. Will cheap and plentiful sunpower facilitate an overdue shift in the distribution of resources and rights, or will it only rearm and consolidate the techno-capitalists as Victoria’s heirs? This is not to disparage the good will, cleverness and hard work of those trying desperately to bring about a transition to renewable energy, but it matters how we imagine that transition and its relationship to complex global legacies of exploitation and oppression. Solar panels are as ubiquitous in games today as they are in many European towns and cities: you’ll accessorise your home with them in Animal Crossing and crawl beneath them in The Last of Us. A handful, like Astroneer, even feature working, self-angling panels corresponding to an in-game sun, but I’ve yet to play one that really thinks about where solar panels come from. They’re beautiful objects and hopeful things, devolving electricity generation from the oligarch to the community and the individual household, but this is hope mixed with amnesia. As Rhys Williams argues in a comprehensive assessment of the “solarpunk” genre, cosy, high-tech yet rustic depictions of solar-powered futures often erase the fact that solar panels are, right now, products of the fossil fuel economy: there’s no other way of manufacturing them at scale. This sanitisation of solar power in fiction is attractive to technologists seeking to greenwash their operations while waving aside the inequalities of the so-called free market. If solarpunk dreams of a healthier post-capitalist world, a different story is told by how it has been embraced by marketing agencies as the latest feelgood aesthetic. It’s even been used to advertise yoghurt. Where solar promises to bestow energy anywhere, fusion is centralised. It’s presented as an extension of 20th century energy infrastructure, broadly conceived according to the existing model of power plants built outside more affluent populated areas and supplying electricity to them “unseen”. As such, it represents the smallest threat to the status quo, for all those promises of “near-limitless” output - or at least, that’s the conclusion you might derive from certain urban management sims. Much like Dyson Spheres in Stellaris, fusion power plants in City: Skylines are late-game capstones or “Monuments” for the most developed cities. You’ll need to populate all nine map squares and assemble a host of unique buildings, ranging from the Science Center to cultural landmarks such as the Modern Art Museum, before you can make the jump to fusion. Sunpower doesn’t transform the cities of City: Skylines, in short; it only completes them, fixing their guiding ideas about civilisation into a triumphal form. Unsurprisingly, videogames also deal in the possibile military value of solar and fusion energy. Depictions of handheld fusion rifles in games such as Destiny aren’t as fanciful as they seem: Lockheed Martin has filed patents for reactors small enough to fit inside aircraft carriers and even fighter jets. Solar has less military potential than fusion, for obvious reasons, but there have been efforts to weaponise reflected sunlight much as, according to legend, the philosopher Archimedes used it to incinerate attacking ships during the siege of Syracuse. Among the more outlandish Nazi R&D projects was an Archimedean “sun gun” - an orbiting mirror three and a half miles square miles in size, capable of concentrating the sun’s rays into a mass-destructive beam. These bizarre wartime experiments are, of course, catnip to the creators of Wolfenstein. In the 2009 game, recurring antagonist Deathshead seeks to funnel the Black Sun’s energy into a zeppelin-mounted cannon. The Nazi death mirror also features in the MachineGames reboots. But the videogame “sun gun” I remember most vividly is that of Boktai, a Gameboy Advance series with a cartridge sensor that “converts” ultraviolet light into energy bullets and currency. However straightforward the in-game applications (vapourising vampires), Boktai’s idea of sunpower has a certain transgressive promise, next to the kinds of energy futures envisaged by management sims or big-budget sci-fi shooters. It gently encourages you to rediscover your physical and social surroundings as you search for ideal lighting conditions, anticipating the uneven subversiveness of smartphone ARGs like Pokemon Go in how it motivates transgressions against taken-for-granted frameworks of property and infrastructure. Both access to and shelter from the sun are a privilege, after all: as Williams puts it, “light does not fall on everyone equally, or with the same consequences”. In the eyes of Himmler and his imitators, the sun is the on-going victory of the same, the basis for thousand-year Reichs of one kind or another. The consumption or replication of stars in the shape of solar or fusion power is garnished with promises of new worlds, but could just as easily perpetuate the unjust one we live in. The sun’s tyranny breeds tyranny below. Could its image prove a door to another and perhaps healthier dimension? I don’t hold out a lot of hope, myself. But in bleak times, there is something invigorating about the sun’s intransigence. It might not be a source of “Universe Matrices”, but it’s an endless provocation to ask the big questions about why the world is the way it is. In Terry Pratchett’s novel The Light Fantastic, the mega-turtle Great A’Tuin carries the Discworld on a collision course with a giant red star. The Star is more than just a deadly obstacle, bigger than Disc and Turtle rolled together. It’s an existential threat, the demon of modern astrophysics tilted against the quaint medieval cosmology of the Disc with its friendly, miniature, orbiting sun. Under the Star’s expanding influence, magic stops working, and wizards are judged to be charlatans by a homicidal populace. It’s one reality swamping another. The dream nears collapse under the brutal insistence of solar gravity. But much as Pratchett’s ideas about sorcery draw on his career as a press officer for a network of nuclear power stations - home to nuclear reactions more magical, and mundane, than anything you’ll read about in a fantasy novel - so the Disc’s proximity to the Star proves a form of incubation, allowing a new reality to be born. In this lies the forever rekindled hope: if we can stay with the sun for long enough, weather its darkness for long enough, what other kinds of matter could we be?