Why was it nearly canned? Because “it was going nowhere and it was awful” - Penn isn’t one for mincing his words. “I don’t know why I used to defend it every week,” he says. “I think I just believed that it could be something, as did Sam Houser who used to work there as well … he was one of the other few people who believed in it.” (Sam Houser went on to co-found Rockstar with his brother Dan and do very well out of GTA, of course.)

There’s an audible sigh as I ask Gary Penn what was so awful about it, as if it’s painful to remember. “For a start it rarely worked,” he begins. “It would crash constantly - full-on, full-scale crashing, not sort of ‘oh, slightly inconvenient’. You couldn’t play it for more than a few minutes.

“It would have so many crude, really amateur qualities to it, like the physics was terrible and the handling of the cars was terrible. And the game structure as it was then … it was much more regimented. Every conceivable thing you could think about that makes a game work was terrible. And it kept crashing.”

Back then, the game was known as Race n’ Chase and it was just one of many games DMA Design (as the studio was known before it became Rockstar North) was working on. And no one knew it would be a cultural phenomenon. It was just a buggy game that wasn’t fun and was leeching resources. It really did have to be fought for.

Penn remembers the moment things began to change. A programmer called Patt Kerr came up with a new physics model for driving. “It was just this box, I think it left a little trail behind as well to better emphasise the motion, and it fishtailed and skidded around. The first time I saw it I just smiled like a dick,” he says. “And you just go, ‘This is sooo cool.’ I think he put a handbrake in as well so it was sliding around, and you think, ‘I fucking love this, we should put this in.’ I like to think this was me… It may not have been me. But this needs to go into GTA.”

And the moment it did go in, people could begin to see what the fuss was about. Suddenly, it was playable. Suddenly, it was fun.

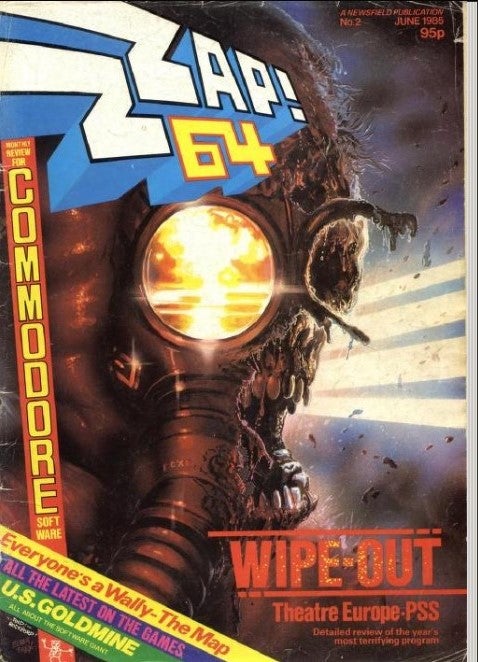

But Gary Penn’s claim to fame doesn’t start with Grand Theft Auto. He was as well known, if not more so, a decade before, as one of the writers of iconic British gaming magazine, Zzap!64.

It was a job he had to win a competition to get. He’d submitted some guides to Personal Computer Games before - he had been obsessing over games ever since Pong! showed up - so when PCG boss Chris Anderson (who went on to found Future Publishing and run TED) decided to run a competition to find ‘Britain’s best gamer’, Penn’s was a name Anderson pulled out.

“We ended up with five of us [going] into the offices for the final of it, and we had to play five new games that hadn’t been released,” Penn says. He can’t remember what they were but they were on a variety of platforms. And he did pretty well, not winning but coming third behind Julian “Jaz” Rignall - another name you might recognise - and someone in first whose name he can’t remember, which feels like a stealth burn to me.

But the results would never be published because the company behind PCG, VNU, folded and shut the magazine down. All was not lost, though, as Chris Anderson decided to start something new and wanted Britain’s best gamers - Penn and Rignall - to write for it. “I got back from a friend’s house late one night and Mum was saying, ‘Oh, there was a guy called Chris Anderson [on the phone for you].’” So he phoned him back and Anderson pitched his idea for a new magazine.

“It was his idea to move away from using journalists,” Penn says, “because as far as he was concerned, they were too stuffy and traditional. He wanted players - gamers - who could write, so I had to do a couple of writing tests and got the job through there.”

The next thing Penn knew, he was moving out of home and down to Yeovil to live with a bunch of like-minded young people and play and write about games all day long. “You’re not gonna say no to that job are you?” No, Gary, I’m not.

It was a formative time for him, and for writing about video games. That personality-led reporting remains to this day, with many teams trying to recreate a sense of extended family playing games alongside you, the reader. Penn remembers working a lot, smoking and drinking a lot, not sleeping a lot, and playing games a lot. And he was intoxicated by the status it was giving him.

“You have this feeling you can do anything,” he says, “absolutely anything, and it was such a beautiful feeling. You’re making it up as you go along, you’re learning stuff, you’re getting really cocky. You’ve got a lot of attention being paid to [you], your opinions are incredibly influential all of a sudden. You’ve got this sort of weird micro-stardom thing going on, which is very peculiar. And you’d go to places and be recognised.”

He would even be spotted years later in a WH Smith in Fife, in Scotland where he lives, by an American tourist circling him near a magazine rack. “Hey! You’re Gary Penn,” the American said. “I was like, ‘Yeahhhh…?’” “Zzap!64 right?!”

But Zzap!64 wouldn’t last. After a few years - and in what seems to be a bit of a pattern - Penn left “in a bit of a huff”, as he describes it. He helped put together some launch issues for magazines like The Games Machine, which he calls a “proto-Edge”, before heading to London where he had a brief stint on pornographic magazine Knave, of all things. “That was interesting,” he says.

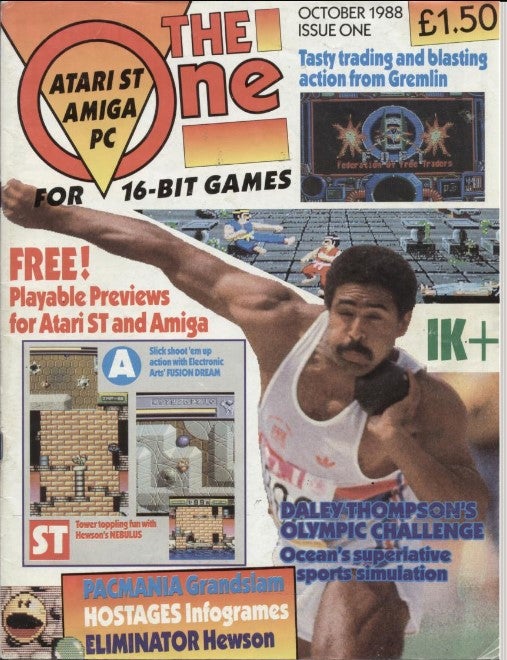

He eventually fell in with publisher EMAP where he experimented with a fortnightly edition of Computer and Video Games (CVG), before eventually being asked what he wanted to do, at which point he came up with an idea for gaming magazine The One. “I think in some respects I was trying to do Edge before Edge but didn’t have the ability to do it,” he says. But after a few successful and award-winning years “I left EMAP in a strop as well”.

It was after this he began the slide into game production. He consulted for a while, wrote game manuals for a while - apparently making such a go of it that people like Archer Maclean asked for him personally to write their manuals (he wrote the Elite 2 manual, the Dune 2 manual, “probably” the Command & Conquer manual) - wrote in-flight magazines. Eventually, it led to a producer role at Konami, and from there to BMG, the record label turned game publisher pouring money into Race n’ Chase/GTA.

He would stay there until the launch of Grand Theft Auto 3, which he remembers being a remake of GTA1, but by then “the Silicon Valley team” was in charge and he was distanced from it. He, on the other hand, was working on what would become Manhunt, the controversy-courting game about being a death row prisoner forced to star in snuff films, where people would try to murder you. “It was initially just a hide and seek game that we were doing - well, a sadistic hide and seek game,” he says. “We were prototyping that.” He was using pen and paper, and coins, to figure out how the game would work.

But working there took its toll on him. DMA was, as he succinctly puts it, “a fucking mess”. “I went through a great deal of stress,” he says. “I nearly broke.” The problem was that DMA had too many projects and was “haemorrhaging money quite horribly”, while not getting anywhere with any of them. There was GTA, Body Harvest, Space Station Silicon Valley, Tanktics, Wild Metal Country, Attack! and Clan Wars, all in development at the same time.

“When you’re on the outside looking in, it’s fantastic,” he says, “all these beautiful original new games coming through. And it’s such a lovely idea that you think it must be such a fantastically creative place to be. And it can be. But equally, when it comes to actually making this shit happen and [getting] work done and finished: Jesus Christ it’s so stressful. It’s so stressful.

“I just burned out,” he says. “When Rockstar bought us I used to get on really well with Sam [Houser] [so] I’m thinking ’this is gonna be fucking awesome’. I just realised…” he trails off with a sigh. “They’re ultimately a good company, they reward well, but they also expect a lot in return. And I was thinking I just don’t want to do this any more. I just felt so burned out by that point.”

This is where Denki comes into his life, the studio he’s been at for more than 22 years now - a remarkable stint. It was set up by DMA people with the idea of making smaller games more quickly and without all the stress. And for a number of years, it really churned them out, making hundreds of interactive TV games for just about every company you can think of.

He didn’t leave triple-A gaming entirely, though. He is one of the few people to have worked on all three Crackdown games. “I got involved right at the beginning, actually,” he says, back when Crackdown was called Car Wars and was a turn-based RPG about vehicular combat. It wasn’t until a designer was messing around with the settings, cranking them up, that the essence of Crackdown’s exaggerated powers was really born.

Denki gradually moved away from interactive TV games, slowing down the amount of releases until it crossed our paths in 2011/2012 with the splendid Quarrel - a mix of Risk and Scrabble. Then in 2019 it hit upon perhaps its most successful game to date: Autonauts, a game about automating tasks in a cosy settlement of your own. It’s got thousands of “overwhelmingly positive” reviews on Steam, and The Guardian loved it. And although it’s not intentionally educational, Autonauts gained a reputation for helping people grasp the fundamentals of programming. It’s even being used in some schools across Europe for exactly that.

Autonauts arrived on console very recently, but more excitingly it will expand this week in a brand new game, Autonauts vs Piratebots. As you can gather, this introduces a threat to the previously carefree mix: pirates, which means you have to defend your settlement against them using a whole load of new researchable tech. It sounds like there’s a lot of new stuff there, and more structure and story than before. Autonauts vs Piratebots comes out this Thursday, 28th July, on PC, with other versions possibly to follow somewhere down the line.

This is where Gary Penn is currently at. He’s someone who’s been a part of games ever since they first began, really, and someone who’s had a hand in shaping some key parts of them. He’s a fascinating person to talk to, not only for the stories he has to tell but for the way he looks at things and thinks about them. And he’s still head over heels about games, most notably having poured more than 3700 hours into Splatoon 2. “Yeah, that’s an obsession,” he happily admits. He’s played the newer GTA games too. His favourite? Vice City.

To hear all of Gary Penn’s story - and I recommend you do! - tune into episode 20 of One-to-one, now available to all premium supporters of Eurogamer. It will be available to everyone else in two weeks’ time.