Having grown up in the area, I was curious to see exactly how my home had been represented. How true would it be to real history? Would it still feel like Gloucestershire? How do you even squash most of England into a game? So I packed up my Viking gear and set sail for the in-game county, eager to learn a little about Gloucestershire’s history along the way through my own research. What I discovered was a slightly hodge-podge version of Gloucestershire that - surprise surprise - isn’t always historically accurate. Yet it also feels wonderfully otherworldly, full of folklore and charming references to the region. It’s also quite Welsh. But more importantly, it somehow feels like home.

Gloucestershire (or “Glowecestrescire” as it’s called in Valhalla) is a relatively high-level area in the Kingdom of Mercia, and the story arc unlocks after a particularly stressful chapter in the game. It feels like something of a getaway holiday for Viking protagonist Eivor: she heads there to help her blacksmith woo a lady, and ends up joining in the local festivities. In fact, the county is presented as a bit of a rural backwater, with Eivor making several blunt comments to this effect. Thanks, Eivor.

For Valhalla’s setting of 873 AD, this would have been a fair assessment. Gloucester’s economy was “mainly domestic and agricultural” at the time, and you get a sense of that from wandering through the city in-game, with most NPCs engaged in bee keeping, domestic chores and maintaining livestock. Gloucester also feels more distinctly Roman than many other cities in Valhalla, reflecting its past as the important Roman fortress and colonia of Glevum. Historians have already cast doubt on the idea Roman ruins would still be standing in fairly good condition by 873 AD, however, so perhaps they would have looked a little more ragged than they appear in-game.

While I initially found it hard to recognise anything from the post-industrialisation Gloucester I know, I found a map estimating the city limits around 1000 AD - the closest I could get to Valhalla’s 873 AD setting - and there are a surprising amount of similarities. The all-important bridge over the Severn leading to Westgate street is visible, along with the positioning of the docks in the south, and a church called St Kenhelm’s is close to the site of modern-day Gloucestershire Cathedral (where an abbey dedicated to Saint Peter was founded around 679 AD). It’s recognisably Gloucester… at least from thousand-year-old estimates.

Where Ubisoft really does push the realms of reality is Gloucestershire’s wider geography, which often feels strangely concertinaed, with some landmarks missing entirely. Much of the western Cotswolds are basically non-existent, and the South Cotswolds are represented by a large hill that’s technically in Wessex. The river Severn is absent, with only the Thames and Avon named, while the town of Winchcombe - which had an Abbey built there in 798 and likely still would have been an important site - has also been left out. In a video game covering most of England, Ubisoft obviously couldn’t do everything, and some sacrifices had to be made.

Despite all this, I could still recognise the Severn Valley and guess at certain landmarks. The unreachable mountains in the west likely represent the Welsh Brecon Beacons, and the large round hills look suspiciously like the Malverns, particularly given the next hills in that direction are the Shropshire Stiperstones. The absence of my hometown of Cheltenham was hardly surprising - it was still only a village at the time - but I was delighted to find one of my local walking routes, Cleeve Hill, which frankly hasn’t changed a great deal from the 9th century.

With little else to do during lockdown, I recently walked up Cleeve Hill to find the Neolithic long barrow Belas Knap, a 5500-year-old burial site, and another named location in Valhalla. Having now visited myself in-person, I can say Ubisoft’s version is seriously convincing. Ubisoft managed to include everything from the bone-filled chambers to the neat stonework at the false entrance. There’s even a note explaining “only those touched may pass through Belas Knap and venture onward to worlds unspoken”. Some believe Belas Knap’s false portal was not made to deter robbers (as there was little of value in the chambers), but was instead used as a spirit door to allow the dead to pass through to accept offerings from descendants. Valhalla’s version does seem to have some treasure remaining, however… which is hidden inside the not-so-false portal. Someone didn’t read the building plans.

Yet the most beautifully-realised part of Gloucestershire, to my mind, is almost certainly the Forest of Dean. Upon stumbling into an area named Aelfwood I realised Ubisoft had recreated Puzzlewood, the ancient wood which has since been used for filming everything from the BBC production of Merlin to Star Wars: The Force Awakens. It’s an otherworldly and mysterious place (also a great spot for ambushing people with a knife), but delve a little deeper and you’ll also discover the Ochre Caves, which are clearly based on the Forest of Dean’s Clearwell Caves. The name is a reference to the mining of ochre at the site (used as a pigment), something which began in the Forest over 4500 years ago, although Valhalla’s cave dwellers seem more preoccupied with pagan rituals. If you fancy doing some virtual tourism of England during lockdown, you could do a lot worse.

As for Gloucestershire’s geographical absences, Ubisoft seems to make up for these in other ways, most noticeably by bringing in local folklore. In Valhalla you can find a location called Sabrina’s Spring, which refers to folklore surrounding the (absent) river Severn. The story goes that the goddess of the river, known as Hafren in Welsh (or latinised as Sabrina), was drowned as a young girl in revenge for an affair between her mother and father. Her stepmother wanted all to remember her father’s infidelity, but instead the river was named after Sabrina, making her immortal. A win for Sabrina, I think?

While not present, the town of Winchcombe gets name-dropped in various notes and letters in Valhalla and also gets the folklore treatment. The in-game locations named St. Kenhelm refer to the legend of Saint Kenelm: a Mercian king’s son who died in 819AD when he was murdered on the orders of his older sister, who wanted the throne. News of the boy’s death was apparently ferried to the Pope by a heavenly dove, and monks from Winchcombe were told to find the body. When the monks brought the body back from the Clent hills, they paused near Winchcombe and a refreshing spring appeared from the ground where they struck their staffs. The boy was buried at Winchcombe Abbey, and the well became a holy site for pilgrims - possibly explaining why Ubisoft decided to name a waterfall and church after the boy-saint in Valhalla.

Speaking of wibbly-wobbly borders, Wales isn’t a visitable location in Valhalla, yet Ubisoft clearly wanted to bring some Welsh influence into the game - and selected border counties like Shropshire (where you fight Welsh King Rhodri the Great) and Gloucestershire as suitable places to do so. I’m half Welsh myself, so can confirm that some have definitely crossed the border. Maen Ceti, the Neolithic burial ground also known as Arthur’s Stone near Swansea, has somehow snuck into the north-western corner of Valhalla’s Gloucestershire. To be fair, Gloucestershire is only thought to have originated as a shire in the 10th century, so perhaps we can forgive Ubisoft for having some slightly strange geography for the sake of dividing the game into neat sections.

Looking beyond the locations, the Welsh connection is definitely a broader theme in Gloucestershire, as the story features a Welsh woman in the form of Gunnar’s fiancé Brigid, while characters warn of Y Ladi Wen (a Welsh apparition that translates to The Woman in White). Welsh love spoons are scattered around, and Eivor partakes in the tradition of Mari Lwyd - which basically involves visiting neighbouring houses with a scary hobby-horse. It’s bundled in with a number of other traditions in Valhalla’s version of Samhain, the Gaelic festival that eventually became modern-day Halloween after merging with the Christian celebration of All Saints’ Day. It seems Ubisoft took quite a few liberties here - Mari Lwyd is also referred to as hoodening, a similar practice from Kent, and Samhain itself actually originated in Ireland. Basically, it’s a big pagan melting pot.

In fact, the main theme of Gloucestershire’s story arc is the tension between Christianity and those clinging to Celtic pagan beliefs. Mercia was one of the kingdoms most resistant to the introduction of Christianity, only officially becoming Christian in 655 with the death of pagan King Penda, which may explain why Ubisoft used Gloucestershire to explore this theme. Tewdwr’s quest to stamp out paganism might have been a little unnecessary in 873 AD, however, as by the mid-700s Christian texts considered paganism to be largely defunct beyond some lingering superstitions and customs, with no mention of any remaining cults. There’s also little evidence that pagans ever sacrificed humans in a wicker man beyond some slightly dodgy Greco-Roman accounts (likely intended to present pagans as barbaric), so it seems Ubisoft probably hammed this up a fair bit.

Anyway, back to the Welsh connection: Valhalla’s Gloucestershire seems to also have a number of references to Arthurian legend, including Arthur’s Stone, a mention of Daughters of Nimue, and a world event called Lady of the Lake. Arthurian references can be found elsewhere in the game, but I like to think Ubisoft’s placement of several Arthurian references near the Welsh border is deliberate. Wales has some strong ties to Arthurian legend: the Welsh poem Y Gododdin contains the earliest known reference to King Arthur, while Merlin was originally a figure in medieval Welsh legend called Myrddin Wyllt. There’s a whole list of Welsh locations said to be linked to King Arthur - take your pick. And if you’re looking for an even more direct link: Modron, a name used in the Gloucestershire story arc, also appears in Welsh Arthurian literature (Modron meaning “divine mother”, an appropriate name for her role in Valhalla).

All of this ties together, I think, in a presentation of Gloucestershire as a fantastical and liminal land. A border county on the edge of a magical wilderness, it’s caught between England and Wales, Christian and pagan. Eivor even remarks that the land feels untamed, as if she had “ridden to the door of another world”. The county is also on the literal border of the game, with a great shiny wall appearing to prevent any travelling to Wales. Perhaps only the Welsh know the secret to crossing.

And that’s before I’ve even mentioned Gloucestershire’s many J.R.R. Tolkien references, a topic on which I’ve already written an article, so here’s a quick recap. As a professor of Anglo-Saxon, in 1928 Tolkien worked on an archaeological dig at a Romano-Celtic temple in the Forest of Dean. The idea of little hobbits living underground likely sprung from the Anglo Saxon belief that the Roman temple was actually made by dwarves, possibly giving Tolkien inspiration for Hobbiton.

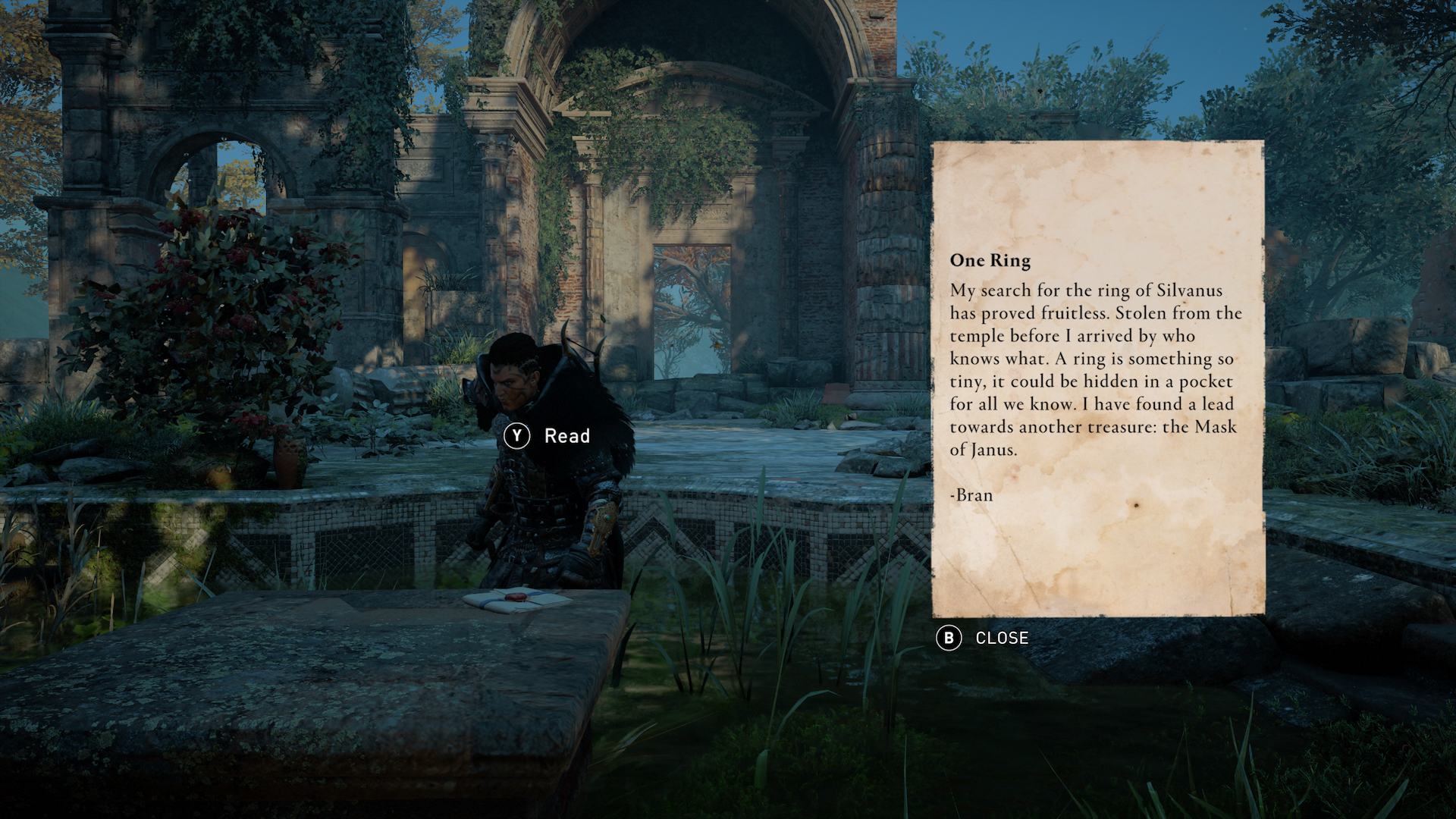

Early excavations at the site had also uncovered a curse tablet, which mentioned another artefact called the Ring of Silvianus. The tablet claimed the ring needed to be returned to the temple in order to break the curse. Which all sounds a little similar to the one ring, does it not? After writing my first article about the hobbit house and ring Easter egg in Valhalla’s Gloucestershire, naturally, I found several more references to the ring; one note directly addressing the disappearance of the Ring of Silvianus (which, in real life, was eventually discovered in Silchester). The placement of the note suggests Valhalla’s Temple of Ceres is the same site Tolkien worked on in the Forest of Dean, and its in-game placement makes geographical sense - although I found little in the ruins to link it to the Celtic deity Nodens.

So Ubisoft’s representation of Gloucestershire is far from historically accurate, but I doubt that was ever Ubisoft’s intention. It’s more a patchwork quilt of real history, folklore and geographical features from the region, with the colours exaggerated for dramatic effect. In that way it’s a little like its source material, the pseudo-historical accounts that emerged in the early medieval period to give Britain its own legends, which tied fact and fiction together to create a compelling and romanticised narrative. But I really do love the local details. Through researching even one county in Valhalla I discovered an astounding amount about my local history, and it’s something I’d recommend to players curious about their own counties. As for me, I’m all too pleased with Ubisoft’s interpretation of Gloucestershire as a mysterious land full of merriment and cider. Just don’t ask me for any magical remedies - you may get more than you bargained for.